Extracted from

AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY

ARMY HISTORICAL SERIES

CHAPTER 25

The Korean War, 1950-1953 After the USSR installed a Communist government in North Korea in September 1948, that government promoted and supported an insurgency in South Korea in an attempt to bring down the recognized government and gain jurisdiction over the entire Korean peninsula. Not quite two years later, after the insurgency showed signs of failing, the northern government undertook a direct attack, sending the North Korea People's Army south across the 38th parallel before daylight on Sunday, June 25, 1950. The invasion, in a narrow sense, marked the beginning of a civil war between peoples of a divided country. In a larger sense, the cold war between the Great Power blocs had erupted in open hostilities.

The Decision for War

The western bloc, especially the United States, was surprised by the North Korean decision. Although intelligence information of a possible June invasion had reached Washington, the reporting agencies judged an early summer attack unlikely. The North Koreans, they estimated, had not yet exhausted the possibilities of the insurgency and would continue that strategy only.

The North Koreans, however, seem to have taken encouragement from the U.S. policy which left Korea outside the U.S. "defense line" in Asia and from relatively public discussions of the economies placed on U.S. armed forces. They evidently accepted these as reasons to discount American counteraction, or their sponsor, the USSR, may have made that calculation for them. The Soviets also appear to have been certain the United Nations would not intervene, for in protest against Nationalist China's membership in the U.N. Security Council and against the U.N.'s refusal to seat Communist China, the USSR member had boycotted council meetings since January 1950 and did not return in June to veto any council move against North Korea.

Moreover, Kim Il Sung, the North Korean Premier, could be confident that his army, a modest force of 135,000, was superior to that of South Korea. Koreans who had served in Chinese and Soviet World War II armies made up a large part of his force. He had 8 full divisions, each including a regiment of artillery; 2 divisions at half strength; 2 separate regiments; an armored brigade with 120 Soviet T34 medium tanks; and 5 border constabulary brigades. He also had 180 Soviet aircraft, mostly fighters and attack bombers, and a few naval patrol craft.

The Republic of Korea (ROK) Army had just 95,000 men and was far less fit. Raised as a constabulary during occupation, it had not in its later combat training under a U.S. Military Advisor Group progressed much beyond company-level exercises. Of its eight divisions, only four approached full strength. It had no tanks and its artillery totaled eighty-nine 105-mm. howitzers. The ROK Navy matched its North Korean counterpart, but the ROK Air Force had only a few trainers and liaison aircraft. U.S. equipment, war-worn when furnished to South Korean forces, had deteriorated further, and supplies on hand could sustain combat operations no longer than fifteen days. Whereas almost $11 million in materiel assistance had been allocated to South Korea in fiscal year 1950 under the Mutual Defense Assistance Program, Congressional review of the allocation so delayed the measure that only a trickle of supplies had reached the country by June 25, 1950.

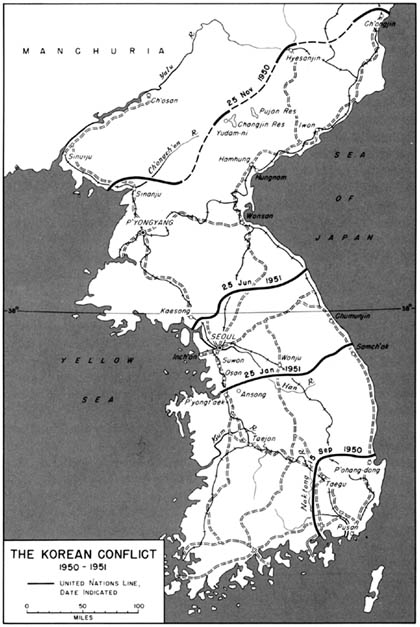

The North Koreans quickly crushed South Korean defenses at the 38th parallel. The main North Korean attack force next moved down the west side of the peninsula toward Seoul, the South Korean capital, thirty-five miles below the parallel, and entered the city on June 28. (Map 45) Secondary thrusts down the peninsula's center and down the east coast kept pace with the main drive. The South Koreans withdrew in disorder, those troops driven out of Seoul forced to abandon most of their equipment because the bridges over the Han River at the south edge of the city were prematurely demolished. The North Koreans halted after capturing Seoul, but only briefly to regroup before crossing the Han.

In Washington, where a 14-hour time difference made it June 24 when the North Koreans crossed the parallel, the first report of the invasion arrived that night. Early on the pith, the United States requested a meeting of the U.N. Security Council. The council adopted a resolution that afternoon demanding an immediate cessation of hostilities and a withdrawal of North Korean forces to the 38th parallel.

Map 45

Map 45 In independent actions on the night of the 25th, President Truman relayed orders to General of the Army Douglas MacArthur at MacArthur's Far East Command headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, to supply ROK forces with ammunition and equipment, evacuate American dependents from Korea, and survey conditions on the peninsula to determine how best to assist the republic further. The President also ordered the U.S. Seventh Fleet from its current location in Philippine and Ryukyu waters to Japan. On the 26th, in a broad interpretation of a U.N. Security Council request for "every assistance" in supporting the June 25 resolution, President Truman authorized General MacArthur to use air and naval strength against North Korean targets below the 38th parallel. The President also redirected the bulk of the Seventh Fleet to Taiwan, where by standing between the Chinese Communists on the mainland and the Nationalists on the island it could discourage either one from attacking the other and thus prevent a widening of hostilities.

When it became clear on June 27 that North Korea would ignore the U.N. demands, the U.N. Security Council, again at the urging of the United States, asked U.N. members to furnish military assistance to help South Korea repel the invasion. President Truman immediately broadened the range of U.S. air and naval operations to include North Korea and authorized the use of U.S. Army troops to protect Pusan, Korea's major port at the southeastern tip of the peninsula. MacArthur meanwhile had flown to Korea and, after witnessing failing ROK Army efforts in defenses south of the Han River, recommended to Washington that a U.S. Army regiment be committed in the Seoul area at once and that this force be built up to two divisions. President Truman's answer on June 30 authorized MacArthur to use all forces available to him.

Thus the United Nations for the first time since its founding reacted to aggression with a decision to use armed force. The United States would accept the largest share of the obligation in Korea but, still deeply tired of war, would do so reluctantly. President Truman later described his decision to enter the war as the hardest of his days in office. But he believed that if South Korea was left to its own defense and fell, no other small nation would have the will to resist aggression, and Communist leaders would be encouraged to override nations closer to U.S. shores. The American people, conditioned by World War II to battle on a grand scale and to complete victory, would experience a deepening frustration over the Korean conflict, brought on in the beginning by embarrassing reversals on the battlefield.

South to the Naktong

Ground forces available to MacArthur included the 1st Cavalry Division and the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions, all under the Eighth U.S. Army in Japan, and the 28th Regimental Combat Team on Okinawa. All the postwar depreciations had affected them. Their maneuverability and firepower were sharply reduced by a shortage of organic units and by a general understrength among existing units. Some weapons, medium tanks in particular, could scarcely be found in the Far East, and ammunition reserves amounted to only a 4s-day supply. By any measurement, MacArthur's ground forces were unprepared for battle. His air arm, Far East Air Forces (FEAF), moreover, was organized for air defense, not tactical air support. Most FEAF planes were short-range jet interceptors not meant to be flown at low altitudes in support of ground operations. Some F-51's in storage in Japan and more of these World War II planes in the United States would prove instrumental in meeting close air support needs. Naval Forces, Far East, MacArthur's sea arm, controlled only five combat ships and a skeleton amphibious force, although reinforcement was near in the Seventh Fleet.

When MacArthur received word to commit ground units, the main North Korean force already had crossed the Han River. By July 3, a westward enemy attack had captured a major airfield at Kimpo and the Yellow Sea port of Inch'on. Troops attacking south repaired a bridge so that tanks could cross the Han and moved into the town of Suwon, twenty-five miles below Seoul, on the 4th.

The speed of the North Korean drive coupled with the unreadiness of American forces compelled MacArthur to disregard the principle of mass and commit units piecemeal to trade space for time. Where to open a delaying action was clear, for there were few good roads in the profusion of mountains making up the Korean peninsula, and the best of these below Seoul, running on a gentle diagonal through Suwon, Osan, Taejon, and Taegu to the port of Pusan in the southeast, was the obvious main axis of North Korean advance. At MacArthur's order, two rifle companies, an artillery battery, and a few other supporting units of the 24th Division moved into a defensive position astride the main road near Osan, ten miles below Suwon, by dawn on July 5. MacArthur later referred to this 540-man force, called Task Force Smith, as an "arrogant display of strength." Another kind of arrogance to be found at Osan was a belief that the North Koreans might ". . . turn around and go back when they found out who was fighting."

Coming out of Suwon in a heavy rain, a North Korean division supported by thirty-three tanks reached and with barely a pause attacked the Americans around 8:00 a.m. on the 5th. The North Koreans lost 4 tanks, 42 men killed, and 85 wounded. But the American force lacked antitank mines, the fire of its recoilless rifles and 2.36-inch rocket launchers failed to penetrate the T34 armor, and its artillery quickly expended the little antitank ammunition that did prove effective. The rain canceled air support, communications broke down, and the task force was, under any circumstances, too small to prevent North Korean infantry from flowing around both its flanks. By midafternoon, Task Force Smith was pushed into a disorganized retreat with over 150 casualties and the loss of all equipment save small arms. Another casualty was American morale as word of the defeat reached other units of the 24th Division then moving into delaying positions below Osan.

The next three delaying actions, though fought by larger forces, had similar results. In each case, North Korean armor or infantry assaults against the front of the American position were accompanied by an infantry double envelopment. By July 15, the 24th Division was forced back on Taejon, sixty miles below Osan, where it initially took position along the Kum River above the town. Clumps of South Korean troops by then were strung out west and east of the division to help delay the North Koreans.

Fifty-three U.N. members meanwhile signified support of the Security Council's June 27 action and twenty-nine of these made specific offers of assistance. Ground, air, and naval forces eventually sent to assist South Korea would represent twenty U.N. members and one nonmember nation. The United States, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Turkey, Greece, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Thailand, the Philippines, Colombia and Ethiopia would furnish ground combat troops. India, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Italy (the non-United Nations country) would furnish medical units. Air forces would arrive from the United States, Australia, Canada, and the Union of South Africa; naval forces would come from the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

The wide response to the council's call pointed out the need for a unified command. Acknowledging the United States as the major contributor, the U.N. Security Council on July 7 asked it to form a command into which all forces would be integrated and to appoint a commander. In the evolving command structure, President Truman became executive agent for the U.N. Security Council. The National Security Council, Department of State, and Joint Chiefs of Staff participated in developing the grand concepts of operations in Korea. In the strictly military channel, the Joint Chiefs issued instructions through the Army member to the unified command in the field, designated the United Nations Command (UNC) and established under General MacArthur.

MacArthur superimposed the headquarters of his new command over that of his existing Far East Command. Air and naval units from other countries joined the Far East Air Forces and Naval Forces, Far East, respectively. MacArthur assigned command of ground troops in Korea to the Eighth Army under Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker, who established headquarters at Taegu on July 15, assuming command of all American ground troops on the peninsula and, at the request of South Korean President Syngman Rhee, of the ROK Army. When ground forces from other nations reached Korea, they too passed to Walker's command.

Between July 14 and 18; MacArthur moved the 25th and 1st Cavalry Divisions to Korea after cannibalizing the 7th Division to strengthen those two units. By then, the battle for Taejon had opened. New 3.5-inch rocket launchers hurriedly airlifted from the United States proved effective against the T34 tanks, but the 24th Division lost Taejon on July 20 after two North Korean divisions established bridgeheads over the Kum River and encircled the town. In running enemy roadblocks during the final withdrawal from town, Maj. Gen. William F. Dean, the division commander, took a wrong turn and was captured some days later in the mountains to the south. When repatriated some three years later, he would learn that for his exploits at Taejon he was one of 131 servicemen awarded the Medal of Honor during the war (Army 78, Marine Corps 42, Navy 7, and Air Force 4).

While pushing the 24th Division below Taejon, the main North Korean force split, one division moving south to the coast, then turning east along the lower coast line. The remainder of the force continued southeast beyond Taejon toward Taegu. Southward advances by the secondary attack forces in the central and eastern sectors matched the main thrust, all clearly aimed to converge on Pusan. North Korean supply lines grew long in the advance, and less and less tenable under heavy UNC air attacks. FEAF meanwhile achieved air superiority, indeed air supremacy, and UNC warships wiped out North Korean naval opposition and clamped a tight blockade on the Korean coast. These achievements and the arrival of the 28th Regimental Combat Team from Okinawa on July 26 notwithstanding, American and South Korean troops steadily gave way. American casualties rose above 6,000 and South Korean losses reached 70,000. By the beginning of August, General Walker's forces held only a small portion of southeastern Korea.

Alarmed by the rapid loss of ground, Walker ordered a stand along a 140-mile line arching from the Korea Strait to the Sea of Japan west and north of Pusan. His U.S. divisions occupied the western arc, basing their position on the Naktong River. South Korean forces, reorganized by American military advisers into two corps headquarters and five divisions, defended the northern segment. A long line and few troops kept positions thin in this "Pusan Perimeter " But replacements and additional units now entering or on the way to Korea would help relieve the problem, and fair interior lines of communications radiating from Pusan allowed Walker to move troops and supplies with facility.

Raising brigades to division status and conscripting large numbers of recruits, many from overrun regions of South Korea, the North Koreans over the next month and a half committed thirteen infantry divisions and an armored division against Walker's perimeter. But the additional strength failed to compensate for the loss of some 58,000 trained men and much armor suffered in the advance to the Naktong. Nor in meeting the connected defenses of the perimeter did enemy commanders recognize the value of massing forces for decisive penetration at one point. They dissipated their strength instead in piecemeal attacks at various points along the Eighth Army line.

Close air support played a large role in the defense of the perimeter. But the Eighth Army's defense really hinged on a shuttling of scarce reserves to block a gap, reinforce a position, or counterattack wherever the threat appeared greatest at a given moment. Timing was the key, and General Walker proved a master of it. His brilliant responses prevented serious enemy penetrations and inflicted telling losses that steadily drew off North Korean offensive power. His own strength meanwhile was on the rise. By mid-September, he had over 500 medium tanks. Replacements arrived in a steady flow and additional units came in: the 5th Regimental Combat Team from Hawaii, the 2d Infantry Division and 1st Provisional Marine Brigade from the United States, and a British infantry brigade from Hong Kong. Thus, as the North Koreans lost irreplaceable men and equipment, UNC forces acquired an offensive capability.

North to the Parallel

Against the gloomy prospect of trading space for time, General MacArthur, at the entry of U.S. forces into Korea, had perceived that the deeper the North Koreans drove, the more vulnerable they would become to an amphibious envelopment. He began work on plans for such a blow almost at the start of hostilities, favoring Inch'on, the Yellow Sea port halfway up the west coast, as the landing site. Just twenty-five miles east lay Seoul where Korea's main roads and rail lines converged. A force landing at Inch'on would have to move inland only a short distance to cut North Ko rean supply routes, and the recapture of the capital city also could have a helpful psychological impact. Combined with a general northward advance by the Eighth Army, a landing at Inch'on could produce decisive results. Enemy troops retiring before the Eighth Army would be cut off by the amphibious force behind them or be forced to make a slow and difficult withdrawal through the mountains farther east.

Though pressed in meeting Eighth Army troop requirements, MacArthur was able to shape a two-division landing force. He formed the headquarters of the X Corps from members of his own staff, naming his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, as corps commander. He rebuilt the 7th Division by giving it high priority on replacements from the United States and by assigning it 8,600 South Korean recruits. The latter measure was part of a larger program, called the Korean Augmentation to the United Stat es Army, in which South Korean troops were placed among almost all American units. At the same time, he acquired from the United States the greater part of the 1st Marine Division, which he planned to fill out with the Marine brigade currently in the Pusan Perimeter. The X Corps, with these two divisions, was to make its landing as a separate force, not as part of the Eighth Army.

MacArthur's superiors and the Navy judged the Inch'on plan dangerous. Naval officers considered the extreme Yellow Sea tides, which range as much as thirty feet, and narrow channel approaches to Inch'on as big risks to shipping. Marine officers saw danger in landing in the middle of a built-up area and in having to scale high sea walls to get ashore. The Joint Chiefs of Staff anticipated serious consequences if Inch'on were strongly defended since MacArthur would be committing his last major reserves at a time when no more General Reserve units in the United States were available for shipment to the Far East. Four National Guard divisions had been federalized on September 1, but none of these was yet ready for combat duty; and, while the draft and call-ups of members of the Organized Reserve Corps were substantially increasing the size of the Army, they offered MacArthur no prospect of immediate reinforcement. But MacArthur was willing to accept the risks.

In light of the uncertainties MacArthur's decision was a remarkable gamble, but if results are what count his action was one of exemplary boldness. The X Corps swept into Inch'on on September 15 against light resistance and, though opposition stiffened, steadily pushed inland over the next two weeks. One arm struck south and seized Suwon while the remainder of the corps cleared Kimpo Airfield, crossed the Han, and fought through Seoul. MacArthur, with dramatic ceremony, returned the capital city to President Rhee on September 29.

General Walker meanwhile attacked out of the Pusan Perimeter on September 16. His forces gained slowly at first; but on September 23, after the portent of Almond's envelopment and Walker's frontal attack became clear, the North Korean forces broke. The Eighth Army, by then organized as four corps, two U.S. and two ROK, rolled forward in pursuit, linking with the X Corps on September 26. About 30,000 North Korean troops escaped above the 38th parallel through the eastern mountains. Several thousand more bypassed in the pursuit hid in the mountains of South Korea to fight as guerrillas. But by the end of September the North Korea People's Army ceased to exist as an organized force anywhere in the southern republic.

North to the Yalu

President Truman, to this point, frequently had described the American-led effort in Korea as a "police action," a euphemism for war that produced both criticism and amusement. But the President's term was an honest reach for perspective. Determined to halt the aggression, he was equally determined to limit hostilities to the peninsula and to avoid taking steps that would prompt Soviet or Chinese participation. By western estimates, Europe with its highly developed industrial resources, not Asia, held the high place on the Communist schedule of expansion; hence, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance needed the deterrent strength that otherwise would be drawn off by a heavier involvement in the Far East.

On this and other bases, a case could be made for halting MacArthur's forces at the 38th parallel. In re-establishing the old border, the UNC had met the U.N. call for assistance in repelling the attack on South Korea. In an early statement, Secretary of State Acheson had said the United Nations was intervening ". . . solely for the purpose of restoring the Republic of Korea to its status prior to the invasion from the north." A halt, furthermore, would be consistent with the U.S. policy of containment.

There was, on the other hand, substantial military reason to carry the war into North Korea. Failure to destroy the 30,000 North Korean troops who had escaped above the parallel and an estimated 30,000 more in northern training camps, all told the equivalent of six divisions, could leave South Korea in little better position than before the start of hostilities. Complete military victory, by all appearances within easy grasp, also would achieve the longstanding U.S. and U.N. objective of reunifying Korea. Against these incentives had to be balanced warnings of sorts against a UNC entry into North Korea from both Communist China and the USSR in August and September. But these were counted as attempts to discourage the UNC, not as genuine threats to enter the war, and on September 27 President Truman authorized MacArthur to send his forces north, provided that by the scheduled time there had been no major Chinese or Soviet entry into North Korea and no announcement of intended entry. As a further safeguard, MacArthur was to use only Korean forces in extreme northern territory abutting the Yalu River boundary with Manchuria and that in the far northeast along the Tumen River boundary with the USSR. Ten days later, the U.N. General Assembly voted for the restoration of peace and security throughout Korea, thereby giving tacit approval to the UNC's entry into North Korea.

On the east coast, Walker's ROK I Corps crossed the parallel on October 1 and rushed far north to capture Wonsan, North Korea's major seaport, on the 10th. The ROK II Corps at nearly the same time opened an advance through central North Korea; and on October 9, after the United Nations sanctioned crossing the parallel, Walker's U.S. I Corps moved north in the west. Against slight resistance, the U.S. I Corps cleared P'yongyang, the North Korean capital city, on October 19 and in five days advanced to the Ch'ongch'on River within fifty miles of the Manchurian border. The ROK II Corps veered northwest to come alongside. To the east, past the unoccupied spine of the axial Tachaek Mountains, the ROK I Corps by October 24 moved above Wonsan, entering Iwon on the coast and approaching the huge Changjin Reservoir in the Taebaeks.

The outlook for the UNC in the last week of October was distinctly optimistic, despite further warnings emanating from Communist China. Convinced by all reports, including one from MacArthur during a personal conference at Wake Island on October 15, that the latest Chinese warnings were more saber-rattling bluffs, President Truman revised his instructions to MacArthur only to the extent that if Chinese forces should appear in Korea MacArthur should continue his advance if he believed his forces had a reasonable chance of success.

In hopes of ending operations before the onset of winter, MacArthur on October 24 ordered his ground commanders to advance to the northern border as rapidly as possible and with all forces available. In the west, the Eighth Army sent several columns toward the Yalu, each free to advance as fast and as Or as possible without regard for the progress of the others. The separate X Corps earlier had prepared a second amphibious assault at Wonsan but needed only to walk ashore since the ROK I Corps had captured the landing area. General Almond, adding the ROK I Corps to his command upon landing, proceeded to clear northeastern Korea, sending columns up the coast and through the mountains toward the Yalu and the Changjin Reservoir. In the United States, a leading newspaper expressed the prevailing optimism with the editorial comment that "Except for unexpected developments ... we can now be easy in our minds as to the military outcome."

UNC forces moved steadily along both coasts, and one interior ROK regiment in the Eighth Army zone sent reconnaissance troops to the Yalu at the town of Ch'osan on October 26. But almost everywhere else the UNC columns encountered stout resistance and, on October 25, discovered they were being opposed by Chinese. "Unexpected developments" had occurred.

In the X Corps zone, Chinese stopped a ROK column on the mountain road leading to the Changjin Reservoir. American marines relieved the South Koreans and by November 6 pushed through the resistance within a few miles of the reservoir, whereupon the Chinese broke contact. In the Eighth Army zone, the first Chinese soldier was discovered among captives taken on October 25 by South Koreans near Unsan northwest of the Ch'ongch'on River. In the next eight days, Chinese forces dispersed the ROK regiment whose troops had reached the Yalu, severely punished a regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division when it came forward near Unsan, and forced the ROK II Corps into retreat on the Eighth Army right. As General Walker fell back to regroup along the Ch'ongch'on, Chinese forces continued to attack until November 6, then, as in the X Corps sector, abruptly broke contact.

At first it appeared that individual Chinese soldiers, possibly volunteers, had reinforced the North Koreans. By November 6, three divisions (10,000 men each) were believed to be in the Eighth Army sector and two divisions in the X Corps area. The estimate rose higher by November 24, but not to a point denying UNC forces a numerical superiority nor to a figure indicating full-scale Chinese intervention.

Some apprehension over a massive Chinese intervention grew out of knowledge that a huge Chinese force was assembled in Manchuria. The interrogation of captives, however, did not convince the UNC that there had been a large Chinese commitment; neither did aerial observation of the Yalu and the ground below the river; and the voluntary withdrawal from contact on 6 November seemed no logical part of a full Chinese effort. General MacArthur felt that the auspicious time for intervention in force had long passed; the Chinese would hardly enter when North Korean forces were ineffective rather than earlier when only a little help might have enabled the North Koreans to conquer all of South Korea. He appeared convinced, furthermore, that the United States would respond with all power available to a massive intervention and that this certainty would deter Chinese leaders who could not help but be aware of it. In an early November report to Washington, he acknowledged the possibility of full intervention, but pointed out that ". . . there are many fundamental logical reasons against it and sufficient evidence has not yet come to hand to warrant its immediate acceptance." His reports by the last week of the month indicated no change of mind.

Intelligence evaluations from other sources were similar. As of November 24, the general view in Washington was that ". . . the Chinese objective was to obtain U.N. withdrawal by intimidation and diplomatic means, but in case of failure of these means there would be increasing intervention. Available evidence was not considered conclusive as to whether the Chinese Communists were committed to a full-scale offensive effort." In the theater, the general belief was that future Chinese operations would be defensive only, that the Chinese units in Korea were not strong enough to block a UNC advance, and that UNC airpower could prevent any substantial Chinese reinforcement from crossing the Yalu. UNC forces hence resumed their offensive. There was, in any event MacArthur said, no other way to obtain ". . . an accurate measure of enemy strength...."

In northeastern Korea, the X Corps, now strengthened by the arrival of the 3d Infantry Division from the United States, resumed its advance on November II. In the west, General Walker waited until the with to move the Eighth Army forward from the Ch'ongch'on while he strengthened his attack force and improved his logistical support. Both commands made gains. Part of the U.S. 7th Division, in the X Corps zone, actually reached the Yalu at the town of Hyesanjin. But during the night of November 25 strong Chinese attacks hit the Eighth Army's center and right; on the 27th the attacks engulfed the leftmost forces of the X Corps at the Changjin Reservoir; and by the 28th UNC positions began to crumble.

MacArthur now had a measure of Chinese strength. Around 200,000 Chinese of the XIII Army Group stood opposite the Eighth Army. With unexcelled march and bivouac discipline, this group, with eighteen divisions plus artillery and cavalry units, had entered Korea undetected during the last half of October. The IX Army Group with twelve divisions next entered Korea, moving into the area north of the Changjin Reservoir opposite the X Corps. Hence, by November 24 more than 300,000 Chinese combat troops were in Korea.

"We face an entirely new war," MacArthur notified Washington on November 28. On the following day he instructed General Walker to make whatever withdrawals were necessary to escape being enveloped by Chinese pushing hard and deep through the Eighth Army's eastern sector, and ordered the X Corps to pull into a beachhead around the east coast port of Hungnam, north of Wonsan.

The New War

In the Eighth Army's withdrawal from the Ch'ongch'on, a strong roadblock set below the town of Kunu-ri by Chinese attempting to envelop Walker's forces from the east caught and severely punished the U.S. 2d Division, last away from the river. Thereafter, at each reported approach of enemy forces, General Walker ordered another withdrawal before any solid contact could be made. He abandoned P'yongyang on December 5, leaving 8,000 to 10,000 tons of supplies and equipment broken up or burning inside the city. By December 15, he was completely out of contact with the Chinese and was back at the 38th parallel where he began to develop a coast-to-coast defense line.

In the X Corps' withdrawal to Hungnam, the center and rightmost units experienced little difficulty. But the 1st Marine Division and two battalions of the 7th Division retiring from the Changjin Reservoir encountered Chinese positions overlooking the mountain road leading to the sea. After General Almond sent Army troops inland to help open the road, the Marine-Army force completed its move to the coast on December 11. General MacArthur briefly visualized the X Corps beachhead at Hungnam as a "geographic threat" that could deter Chinese to the west from deepening their advance. Later, with prompting from the Joint Chiefs, he ordered the X Corps to withdraw by sea and proceed to Pusan, where it would become part of the Eighth Army. Almond started the evacuation on the 11th, contracting his Hungnam perimeter as he loaded troops and materiel aboard ships in the harbor. With little interference from enemy forces, he completed the evacuation and set sail for Pusan on Christmas Eve.

On the day before, General Walker was killed in a motor vehicle accident while traveling north from Seoul toward the front. Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway hurriedly flew from Washington to assume command of the Eighth Army. After conferring in Tokyo with MacArthur, who instructed General Ridgway to hold a position as far north as possible but in any case to maintain the Eighth Army intact, the new army commander reached Korea on the 26th.

Ridgway himself wanted at least to hold the Eighth Army in its position along the 38th parallel and if possible to attack. But his initial inspection of the front raised serious doubts. The Eighth Army, he learned, was clearly a dispirited command, a result of the hard Chinese attacks and the successive withdrawals of the past month. He also discovered much of the defense line to be thin and weak. The Chinese XIII Army Group meanwhile appeared to be massing in the west for a push on Seoul, and twelve reconstituted North Korean divisions seemed to be concentrating for an attack in the central region. From all evidence available, the New Year holiday seemed a logical date on which to expect the enemy's opening assault.

Holding the current line, Ridgway judged, rested both on the early commitment of reserves and on restoring the Eighth Army's confidence. The latter, he believed, depended mainly on improving leadership throughout the command. But it was not his intention to start "lopping off heads." Before he would relieve any commander, he wanted personally to see the man in action, to know that the relief would not adversely affect the unit involved, and indeed to be sure he had a better commander available. For the time being, he intended to correct deficiencies in leadership by working "on and through" the incumbent corps and division commanders.

To strengthen the line, he committed the 2d Division to the central sector where positions were weakest, even though that unit had not fully recovered from losses in the Kunu-ri roadblock, and pressed General Almond to quicken the preparation of the X Corps whose forces needed refurbishing before moving to the front. Realizing that time probably was against him, he also ordered his western units to organize a bridgehead above Seoul, one deep enough to protect the Han River bridges, from which to cover a withdrawal below the city should an enemy offensive compel a general retirement.

Enemy forces opened attacks on New Year's Eve, directing their major effort toward Seoul. When the offensive gained momentum, Ridgway ordered his western forces back to the Seoul bridgehead and pulled the rest of the Eighth Army to positions roughly on line to the east. After strong Chinese units assaulted the bridgehead, he withdrew to a line forty miles below Seoul. In the west, the last troops pulled out of Seoul on January 4, 1951, demolishing the Han bridges on the way out, as Chinese entered the city from the north.

Only light Chinese forces pushed south of the city and enemy attacks in the west diminished. In central and eastern Korea, North Korean forces pushed an attack until mid-January. When pressure finally ended ale along the front, reconnaissance patrols ordered north by Ridgway to maintain contact encountered only light screening forces, and intelligence sources reported that most enemy units had withdrawn to refit. It became clear to Ridgway that a primitive logistical system permitted enemy forces to undertake offensive operations for no more than a week or two before they had to pause for replacements and new supplies, a pattern he exploited when he assigned his troops their next objective. Land gains, he pointed out, would have only incidental importance. Primarily, Eighth Army forces were to inflict maximum casualties on the enemy with minimum casualties to themselves. "To do this," Ridgway instructed, "we must wage a war of maneuver—slashing at the enemy when he withdraws and fighting delaying actions when he attacks."

Whereas Ridgway was now certain his forces could achieve that objective, General MacArthur was far less optimistic. Earlier, in acknowledging the Chinese intervention, he had notified Washington that the Chinese could drive the UNC out of Korea unless he received major reinforcement. At the time, however, there was still only a slim reserve of combat units in the United States. Four more National Guard divisions were being brought into federal service to build up the General Reserve, but not with commitment in Korea in mind. The main concern in Washington was the possibility that the Chinese entry into Korea was only one part of a USSR move toward global war, a concern great enough to lead President Truman to declare a state of national emergency on December 16. Washington officials, in any event, considered Korea no place to become involved in a major war. For all of these reasons, the Joint Chiefs of Staff notified MacArthur that a major build-up of UNC forces was out of the question. MacArthur was to stay in Korea if he could, but should the Chinese drive UNC forces back on Pusan, the Joint Chiefs would order a withdrawal to Japan.

Contrary to the reasoning in Washington, MacArthur meanwhile proposed four retaliatory measures against the Chinese: blockade the China coast, destroy China's war industries through naval and air attacks, reinforce the troops in Korea with Chinese Nationalist forces, and allow diversionary operations by Nationalist troops against the China mainland. These proposals for escalation received serious study in Washington but were eventually discarded in favor of sustaining the policy of confining the fighting to Korea.

Interchanges between Washington and Tokyo next centered on the timing of a withdrawal from Korea. MacArthur believed Washington should establish all the criteria of an evacuation, whereas Washington wanted MacArthur first to provide the military guidelines on timing. The whole issue was finally settled after General J. Lawton Collins, Army Chief of Staff, visited Korea, saw that the Eighth Army was improving under Ridgway's leadership, and became as confident as Ridgway that the Chinese would be unable to drive the Eighth Army off the peninsula. "As of now," General Collins announced on January 15, "we are going to stay and fight."

Ten days later, Ridgway opened a cautious offensive, beginning with attacks in the west and gradually widening them to the east. The Eighth Army advanced slowly and methodically, ridge by ridge, phase line by phase line, wiping out each pocket of resistance before moving farther north. Enemy forces fought back vigorously and in February struck back in the central region. During that counterattack, the 23d Regiment of the 2d Division successfully defended the town of Chipyong-ni against a much larger Chinese force, a victory that to Ridgway symbolized the Eighth Army's complete recovery of its fighting spirit. After defeating the enemy's February effort, the Eighth Army again advanced steadily, recaptured Seoul by mid-March, and by the first day of spring stood just below the 38th parallel.

Intelligence agencies meanwhile uncovered evidence of rear area offensive preparations by the enemy. In an attempt to spoil those preparations, Ridgway opened an attack on April 5 toward an objective line, designated Kansas, roughly ten miles above the 38th parallel. After the Eighth Army reached Line Kansas, he sent a force toward an enemy supply area just above Kansas in the west-central zone known as the Iron Triangle. Evidence of an imminent enemy offensive continued to mount as these troops advanced. As a precaution, Ridgway on April 12 published a plan for orderly delaying actions to be fought when and if the enemy attacked, an act, events proved, that was one of his last as commander of the Eighth Army.

Plans being written in Washington in March, had they been carried out, well might have kept the Eighth Army from moving above the 38th parallel toward Line Kansas. For as a gradual development since the Chinese intervention, the United States and other members of the UNC coalition by that time were willing, as they had not been the past autumn, to accept the clearance of enemy troops from South Korea as a suitable final result of their effort. On March 20, the Joint Chiefs notified MacArthur that a Presidential announcement was being drafted which would indicate a willingness to negotiate with the Chinese and North Koreans to make "satisfactory arrangements for concluding the fighting," and which would be issued "before any advance with major forces north of 38th Parallel." Before the President's announcement could be made, however, MacArthur issued his own offer to enemy commanders to discuss an end to the fighting, but it was an offer that placed the UNC in the role of victor and which indeed sounded like an ultimatum. "The enemy . . . must by now be painfully aware," MacArthur said in part, "that a decision of the United Nations to depart from its tolerant effort to contain the war to the area of Korea, through an expansion of our military operations to its coastal areas and interior bases, would doom Red China to the risk of imminent military collapse." President Truman considered the statement at cross-purposes with the one he was to have issued and so canceled his own. Hoping the enemy might sue for an armistice if kept under pressure, he permitted the question of crossing the 38th parallel to be settled on the basis of tactical considerations. Thus it became Ridgway's decision; and the parallel would not again assume political significance.

President Truman had in mind, after the March episode, to relieve MacArthur but had yet to make a final decision when the next incident occurred. On April 5, Joseph W. Martin, Republican leader in the House of Representatives, rose and read MacArthur's response to a request for comment on an address Martin had made suggesting the use of Nationalist Chinese forces to open a second front. In that response, MacArthur said he believed in "meeting force with maximum counterforce," and that the use of Nationalist Chinese forces fitted that belief. Convinced, also, that ". . . if we lose this war to Communism in Asia the fall of Europe is inevitable, win it and Europe most probably would avoid war . . . ," he added that there could be " . . . no substitute for victory . . ." in Korea.

President Truman could not accept MacArthur's open disagreement with and challenge of national policy. There were also grounds for a charge of insubordination, since MacArthur had not cleared his March 24 statement or his response to Representative Martin with Washington, contrary to a Presidential directive issued in December requiring prior clearance of all releases touching on national policy. Concluding that MacArthur was ". . . unable to give his wholehearted support to the policies of the United States government and of the United Nations in matters pertaining to his official duties," President Truman recalled MacArthur on April 11 and named General Ridgway as successor. MacArthur returned to the United States to receive the plaudits of a nation shocked by the relief of one of its greatest military heroes. Before the Congress and the public he defended his own views against those of the Truman Administration. The controversy stirred up was to endure for many months, but in the end the nation accepted the fact that, whatever the merit of MacArthur's arguments, the President as Commander in Chief had a right to relieve him.

Before transferring from Korea to Tokyo, General Ridgway on April 14 turned over the Eighth Army to Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet. Eight days later twenty-one Chinese and nine North Korean divisions launched strong attacks in western Korea and lighter attacks in the east, with the major effort aimed at Seoul. General Van Fleet withdrew through successive delaying positions to previously established defenses a few miles north of Seoul where he finally contained the enemy advance. When enemy forces withdrew to refurbish, Van Fleet laid plans for a return to Line Kansas but then postponed the countermove when his intelligence sources indicated he had stopped only the first effort of the enemy offensive.

Enemy forces renewed their attack after darkness on May 15. Whereas Van Fleet had expected the major assault again to be directed against Seoul, enemy forces this time drove hardest in the east central region. Adjusting units to place more troops in the path of the enemy advance and laying down tremendous amounts of artillery fire, Van Fleet halted the attack by May 20 after the enemy had penetrated thirty miles. Determined to prevent the enemy from assembling strength for another attack, he immediately ordered the Eighth Army forward. The Chinese and North Koreans, disorganized after their own attacks, resisted only where their supply installations were threatened. Elsewhere, the Eighth Army advanced with almost surprising ease and by May 31 was just short of Line Kansas. The next day Van Fleet sent part of his force toward Line Wyoming whose seizure would give him control of the lower portion of the Iron Triangle. The Eighth Army occupied both Line Kansas and the Wyoming bulge by mid-June.

Since the Kansas-Wyoming line traced ground suitable for a strong defense, it was the decision in Washington to hold that line and wait for a bid for armistice negotiations from the Chinese and North Koreans, to whom it should be clear by this time that their committed forces lacked the ability to conquer South Korea. In line with this decision, Van Fleet began to fortify his positions. Enemy forces meanwhile used the respite from attack to recoup heavy losses and to develop defenses opposite the Eighth Army. The fighting lapsed into patrolling and small local clashes.